Over the past four decades, Christianity has grown faster in China than anywhere else in the world. Daryl Ireland, a Boston University School of Theology research assistant professor of mission, estimates that the Christian community there has grown from 1 million to 100 million. What led to that explosion, centuries after the first Christian missionaries arrived in China? The BU scholars behind the China Historical Christian Database aim to find out.

The project, which allows researchers to visualize the history of Christianity in modern China, links web-based visualization tools with a database packed with the names and locations of missionaries, churches, schools, hospitals, and publications. Hosted by BU's Center for Global Christianity & Mission, the project launched in 2018 and version 2.0 of the database is scheduled for release in 2023. The new version will double the amount of data previously available, providing approximately four million data points—names, occupations, locations, dates, and more—spanning four centuries (1550–1950).

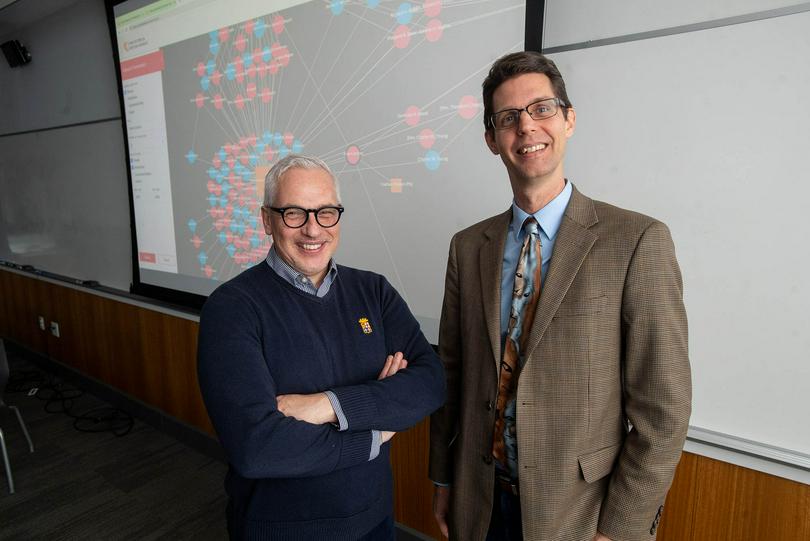

The database began as a relatively modest class project. Alex Mayfield (STH'21) charted early 20th-century Pentecostals in Hong Kong for a history class taught by Eugenio Menegon at the BU Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. When Mayfield mentioned his research to Ireland, the pair began thinking about how to expand the work—by several centuries and across China. Mayfield, Menegon, and Ireland are now the principal investigators for the China Historical Christian Database.

Ireland spoke with The Brink about how the database could help scholars understand the relationships between China and the Western world.

The Brink: What drew you to the study of Christianity in China?

Daryl Ireland: It has such a fascinating and complicated history. You can see the dynamics of Christianity and culture interacting in amazing ways. Sometimes, watching how Christianity becomes embodied in Chinese culture and society provides a mirror for reflecting on the ways in which Christianity in the United States has also shaped and been shaped by the American experience. And then I'm also fascinated that, over the last 40 years, Christianity has grown faster in China than any other place in the world. It's gone from approximately 1 million Christians to around 100 million. This is just an incredible explosion. What set that up? That didn't just come out of nowhere.

The Brink: Why China and why Christianity—is there something about that convergence that's conducive for a digital project?

Daryl Ireland: The length of history—400 years—and the strong record keeping over that time period, both in European languages and in Chinese. We have the opportunity to view this interchange between two world systems from multiple levels, and that makes it really fascinating. We're recording everything we can, from the relationships that missionaries developed in the 16th century to Mao Zedong and his early work for the YMCA. It's an incredibly rich body of material and gives us a really good picture of the relationship between China and the West.

The Brink: What is the data you're collecting and where is it coming from?

Daryl Ireland: Our objective is to map every Christian institution in China, whether it's a church, school, hospital, publishing house, orphanage, or convent. Then we try to identify who worked inside them. We use all kinds of records and sources. One of the simple ones is a Protestant directory of Christian missionaries in China that was published annually in the 20th century. That gave us a rich source of names. Other times, we are looking through diaries, or the preface of a book written by a Chinese literati where he may thank the Christians who first introduced him to certain ideas. So, we draw on a wide variety of sources to put together social networks and spatial maps.

The Brink: Are these sources available online or are you searching physical archives and libraries?

Daryl Ireland: Both. We have been blessed to live in an age where so much has been digitized. But we've also had to digitize an enormous quantity of material, working with institutions around the globe to make it more accessible for our team members. While there are three project leaders, we've had over 100 students work on this project, and they are located on four continents.

The Brink: What's the ideal source for you?

Daryl Ireland: Our dream document gives us maybe the names of people, where they were located, the years they were there, what they were doing—were they a doctor, a nurse, an evangelist?—and possibly some of the people they were connected to. Those are the five big things that we're always searching for. We usually find about three of those five in documents, so there's a lot of triangulation of our various data sources to build out the picture that we're trying to make. We've never found the perfect document.

The Brink: How close are you to the goal of mapping all of these entities?

Daryl Ireland: In terms of foreign missionaries, I think we are probably about 90 percent done. We've got a pretty good dataset of around 30,000 foreigners who were in China during that 400-year period. The much more difficult question is what about the Chinese actors that we're looking for? We've never tried to claim we're going to record every Chinese Christian. That is beyond our scope. But even locating the more visible ones, those who worked in Christian institutions, such as pastors, doctors, publishers—that's still an unknown quantity. How well are we going to be able to piece together the Chinese story? That is the challenge we are addressing now, and it's forcing us to get creative.

The Brink: How do you hope people will use this data?

Daryl Ireland: We've imagined this to be a resource primarily for scholars, but also for students and the general public. We have tried to make the data as accessible as possible. It's free to download and we've created a web interface so that if you don't have the digital skills to write your own database queries, you can still search through the data. What people do with that varies. The general public probably uses it most often for genealogical research. Students or teachers use it in the classroom for a quick visual, like a heat map representation to show where Christianity was most prevalent in China. And scholars use it for all kinds of fascinating things. There is a team at Oxford that is trying to use the data to look at how religions have responded to climate change. They look at times of famines and droughts and watch, on our map, what happens with Christians—do they move into locations that are devastated or do they move out of them? And a team at Harvard Business School has proposed using our map to look at social networks and economic development. They're trying to see whether economic expansion preceded religious expansion, or if economic exchanges began happening through these religious networks.

The Brink: The study of religion doesn't necessarily call to mind data science and big data. Why does this melding of fields make sense?

Daryl Ireland: Digital scholarship and digital tools can enhance our scholarship and our understanding of history and human life. This is a way of doing scholarship that allows us to take massive amounts of data and begin to synthesize them in some really fun and creative ways. And one of the great things about digital resources and digital scholarship is that, when done well, it empowers the user to become the author of history.

The Brink: What comes next with this project?

Daryl Ireland: We decided to get as broad a picture as possible as quickly as possible. Now we are really choosing areas of focus. At the moment, for instance, we are trying to finish off Christian schools in China, so that's where we've invested a lot of our energy. When we're done with that, we will move to another area. At this point, we want our historical questions to begin driving what kind of data we choose to input next.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

The database was launched with seed money from BU's Rafik B. Hariri Institute for Computing and Computational Science & Engineering and received a pilot grant from the BU Center for Innovation in Social Science. In August 2021, the project received a $100,000 Digital Humanities Advancement Grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Originally from The Brink

CCD edited and reprinted with permission