This week, as Stockholm hosts the Ecumenical Week from August 18–24, churches and ecumenical organizations from across the world are gathering for a centennial commemoration of the 1925 Stockholm Conference on Life and Work. The Christian Council of Sweden is welcoming thousands of participants, including church leaders, presenters, and decision-makers, who will join more than 70 seminars, prayer services, and cultural events under the theme "Time for God's Peace."

The Stockholm Conference of 1925, initiated by Archbishop Nathan Söderblom, served as a significant beginning for the modern ecumenical movement. Bishop Dr Jonas Jonson, bishop emeritus of the Diocese of Strängnäs in the Church of Sweden, who has been actively involved in the life and work of the World Council of Churches (WCC) for more than 60 years, traced the history of how the WCC began decades before its official founding in 1948.

Jonson recalled that the vision for what later became the WCC can be traced back to the years before World War I, when a small circle of enthusiastic individuals was committed to fostering Christian unity and social justice. Many of them were parliamentarians and older public figures concerned about poor working conditions and the urgent need for peace in Europe.

In 1914, just as war broke out, 80 of these individuals gathered in Constance, a town on the Swiss-German border, to form what they called an "alliance for promoting friendships among the people." Although they were unable to meet during the war, they maintained contact through extensive correspondence, building personal friendships.

When the war ended, the group reconvened in 1919 in the Netherlands, with Archbishop Nathan Söderblom among them. This time, however, participants were only from neutral countries; it was not yet possible to bring together representatives from former warring nations.

Söderblom came with a bold vision: churches should be represented officially—not merely by private individuals—in a council or assembly that could help Europe emerge from devastation. He also believed this council should act as a unified Christian voice in the peace negotiations and the wider reconstruction of Europe and the world.

Meetings continued, including a small meeting in Paris to draw up an outline. In 1920, a gathering of 100 participants in Geneva addressed practical matters such as the election of delegates and the financing of a larger assembly.

"The Swiss were dead against having any Catholics in this meeting, and the Archbishop of Canterbury had said that he would not back it if there were not both Orthodox and Catholics invited, and Söderblom himself wanted also a full ecumenical spectrum, so there was much dispute about this," said Jonson.

A turning point came when Söderblom established direct contact with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1920, the Patriarchate issued its famous encyclical calling for a "league of churches." Söderblom was the first to respond positively, strengthening ties with the Orthodox. Efforts were also made to include the Catholic Church, though ultimately without success.

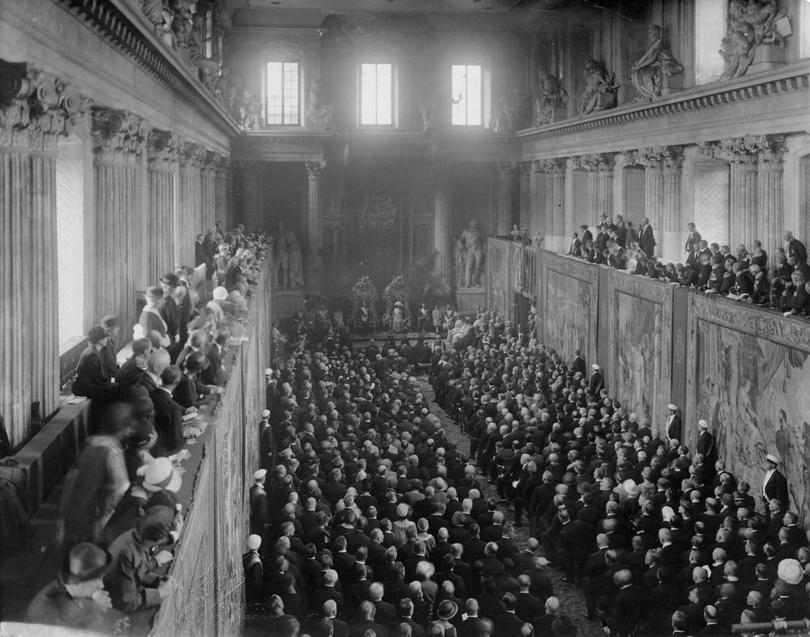

All of this groundwork culminated in the Universal Christian Conference on Life and Work, held in Stockholm in August 1925. It was the result of five years of intensive preparation and delicate diplomacy. For the first time since the war, delegations from former enemy nations—including France, Germany, and Britain—sat together in the same assembly. The conference gathered 600 officially appointed delegates, including 60 women.

Although the Stockholm Conference produced no binding documents—hampered in part by the lack of simultaneous translation—its greatest achievement was that it happened at all.

Jonson added, "The most important thing with the Stockholm Conference was simply that it happened. People met. People talked with each other for the first time after the war. People shared meals. People had a common experience of a beautiful summer week in Stockholm. People came as enemies and left as friends, and the platform was formed for what later became the ecumenical movement."

Then, a Continuation Committee from the Stockholm Conference established an Office for Social Ethics in Geneva—the first center of ecumenical work in Geneva. In the end, the WCC was constituted after the Second World War in 1948, with its headquarters based in Geneva.

"The whole thing was built on a handful of people with initiative, strength, and perseverance," said Jonson.

This article is compiled from content published by the World Council of Churches.